How builders can do so much to reduce embodied carbon

For some time now, Built has swapped traditional emissions-intensive concrete with lower carbon varieties.

This tier 1 builder reasons that by substituting conventional concrete with a 40-45 per cent lower emission mix, its construction projects can slash upfront carbon by as much as 25 per cent. And without a significant impact on cost.

It’s a classic win-win, and Built’s national sustainability manager Clare Gallagher says that replacing the concrete mix has been a big success story for the company and its clients.

“We’ll see even bigger savings across more materials soon as the construction materials manufacturing industry ramps up its ambitions to develop lower carbon products,” she says, pointing to the emerging areas such as green steel and geopolymers.

It’s just one example of the immediate wins the construction and development industry has at its fingertips now to reduce embodied carbon. And there are plenty more, Gallagher says.

It’s why this builder has taken a step out from its internal business focus to invite collaboration with its peers. The idea is to share learnings and data and to find benchmarks that can benefit all contractors, their clients, suppliers and wider stakeholders.

Built has kicked off this initiative with a report, Taking Action on Embodied Carbon, that shares the company’s learnings from the past six years and provides a practical guide on how to take action on reducing upfront carbon. Upfront carbon is the industry defined term to identify the carbon component embedded in building fabric from cradle to practical completion. Embodied carbon refers to carbon emissions from materials such as fixtures and fittings installed during the operational phase of a building.

According to chief executive and managing director Brett Mason, the company has been steadily working on its low carbon ambitions for several years and feels now is the time to share some knowledge with the wider industry, knowing that real reductions can only happen if others join across the supply chain to collaboratively push the envelope of what’s possible.

“We’ve had some really challenging projects in recent times where we’ve taken the initiative to change the way we do things and see if we can start to seriously reduce embodied carbon – and we’re starting to see significant progress,” Mason says.

Projects such as the former substation in Clarence Street that’s now the company’s headquarters and the huge Walker Corporation office towers at Parramatta Square, in Sydney’s second CBD for instance have achieved substantial sustainability gains, he says.

At Clarence Street, Built retained a heritage warehouse and substation building while adding an extension above in the form of a “sculptural art piece” designed by FJMT to achieve a blend of retained building fabric and new premium office space. The sustainability dividend was a 23 per cent reduction in embodied carbon (compared to a reference case).

At the 233 metre high skyscraper at 6 & 8 Parramatta Square, Built reduced cement in concrete mixes and removed superfluous materials, with the result expected to yield an 18 per cent reduction in upfront carbon.

Mason says that across 10 key projects his team has calculated that in the past six years the company has been able to save 74,429 tonnes of upfront carbon – equivalent to the total upfront carbon in a conventional 40 storey concrete building.

At the 233 metre high skyscraper at 6 & 8 Parramatta Square, Built reduced cement in concrete mixes and removed superfluous materials, with the result expected to yield an 18 per cent reduction in upfront carbon.

Mason says that across 10 key projects his team has calculated that in the past six years the company has been able to save 74,429 tonnes of upfront carbon – equivalent to the total upfront carbon in a conventional 40 storey concrete building.

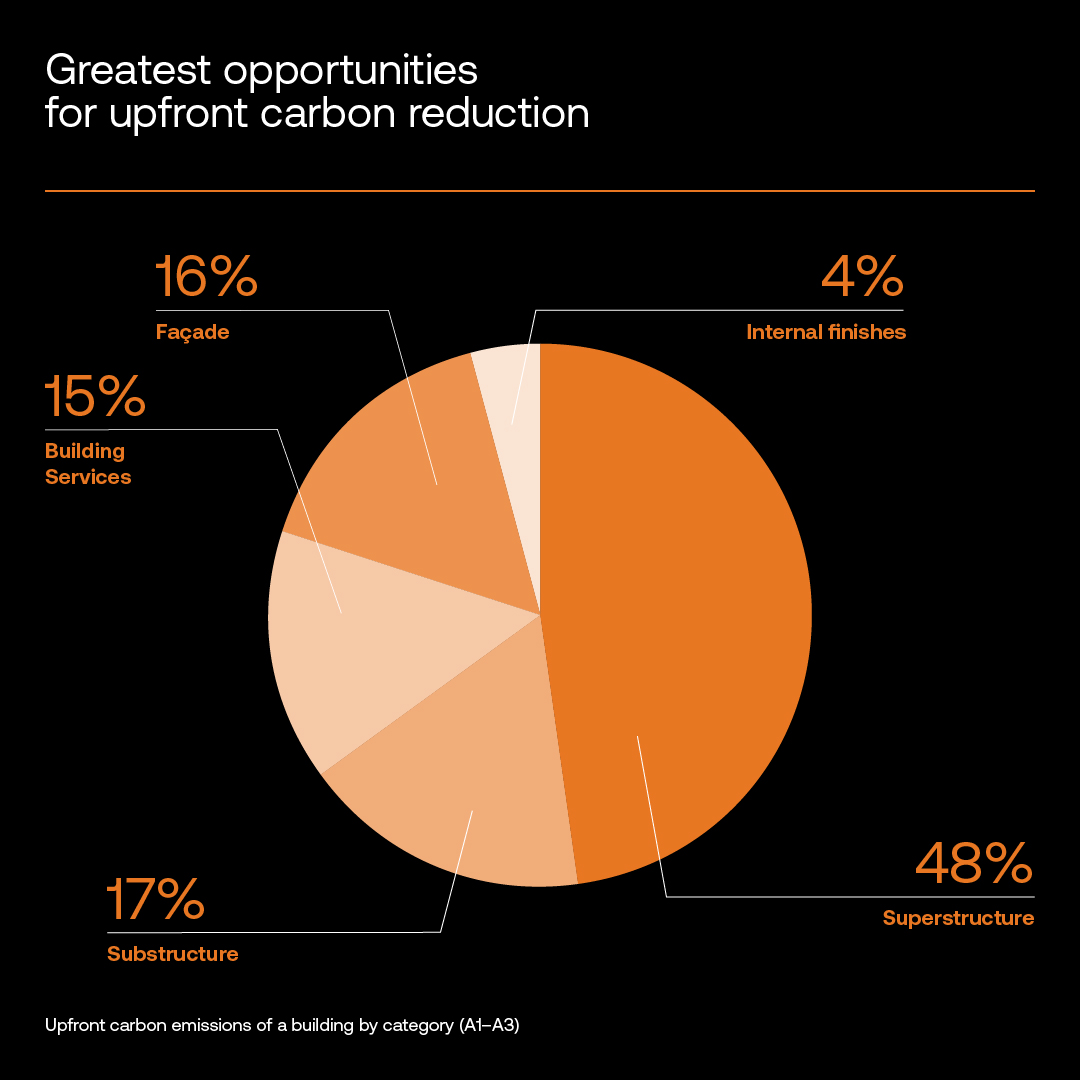

“There is a huge amount of embodied carbon across structures, especially in substructure and, to a lesser extent, façades,” he says.

“And there is an opportunity to challenge thinking by providing our engineers with more latitude in both reducing the quantity of materials used and giving freedom to use alternatives to standard steel and cement.

“If you can keep existing fabric and structure, such as the substation, and maintain quality and structural integrity by using the low carbon products now readily available and challenging where materials can be considered superfluous, you’re already ahead on carbon savings.”

This is a time, Mason points out, where there’s growing focus on how much carbon goes into any building work with the building and construction sector responsible for 39 per cent of all global emissions – 11 per cent from embodied carbon.

It’s a trend that is only going to grow in intensity and priority. The recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change calling Code Red on the climate will reinforce growing demands from the investors and financiers for better performance and transparency from the built environment.

“It’s time builders took a bigger leadership position,” Mason says.

According to Joe Karten, Built’s head of sustainability and social impact, who is co-author of the report with Clare Gallagher, a proactive builder can do a lot to help the environmental profile of its clients and in turn its occupants and investor stakeholders.

“And there is an opportunity to challenge thinking by providing our engineers with more latitude in both reducing the quantity of materials used and giving freedom to use alternatives to standard steel and cement.

“If you can keep existing fabric and structure, such as the substation, and maintain quality and structural integrity by using the low carbon products now readily available and challenging where materials can be considered superfluous, you’re already ahead on carbon savings.”

Leadership starts at the top

Karten says builders are in a unique position in the overall supply chain. “They have the ability to drive positive upfront carbon outcomes through design resolution and materials procurement at key intervention points throughout the development,” he says.

But while Built has taken ownership of the contractor’s role, reducing embodied carbon is an industry-wide responsibility that should start at the top, Karten says.

“If the client drives it in the first instance, and sets design briefs to include targets to reduce embodied carbon, it will shift the whole approach.

“This can embolden architects and engineers to come up with creative low carbon alternatives to the status quo. And this in turn filters down to the builder, where we can look for other design interventions and leverage our supply chain links to procure the lowest carbon materials on offer within budget.”

Karten says there are a few examples in Australia of clients setting benchmarks for embodied carbon – Atlassian, for example, which says it wants a 50 per cent saving for its new headquarters near Central Station.

Recently the GBCA’s new Green Star Buildings tool set a 40 per cent reduction in embodied carbon target.

Targets can provide an effective circuit-breaker to strict code compliant design, Karten says. “Giving licence to structural engineers to make their designs efficient while maintaining safety, will enable further embodied carbon savings to be unlocked.”

A guide to taking action

In a nutshell, Built’s report is a kind of companion piece for builders to an industry-wide paper recently released by the Green Building Council of Australia, Embodied Carbon & Embodied Energy in Australia’s Buildings.

The Built paper focuses on how to take action now, with steps to manage and reduce embodied carbon on a project, while the GBCA report developed in conjunction with thinkstep, delves into why the focus on embodied carbon is becoming critical.

Karten says that in the race to decarbonise global economies to keep the planet at a safe level of warming, any carbon emissions we can control now are particularly valuable.

It’s important that upfront emissions are considered within the overall project context and brief, however, and don’t trump design decisions that might lower operational energy. For instance, triple-glazing has more upfront carbon than single-glazing but the former can save a lot of operational carbon emissions, especially during this transition phase to a fully renewable electricity grid.

A comprehensive life cycle assessment as a key step outlined in the report will keep these competing outcomes in balance.

The report also focuses on the need for an industry agreed methodology to fairly compare carbon savings.

The lack of consistency in benchmarking and reporting data is “a real problem”, Karten says, and it opens the door to “gaming” the results.

Gallagher says that once people “catch the slightest scent of that, they lose trust. That’s why it needs to be standardised.”

Karten says life cycle assessment sophistication is where energy modelling in Australian was 15 or 20 years ago. “It’s come a long way since then and now we are rarely getting buildings that don’t live up to energy performance modelling.”

“We need the same trajectory of LCA adoption, but we can’t wait another 20 years. The only way that will happen is if the whole industry shares its data and collaborates in the spirit of building industry-wide competence.”

This article was first published by The Fifth Estate and has been published with their permission.